The American (2010): A Psychological Analysis

Corbijn's stark thriller follows a solitary operative's final days in Italy, where a life of professional detachment encounters the possibility of connection only at its end.

Introduction

Anton Corbijn's "The American" (2010) is a film that defies easy categorization. On the surface, it presents as a thriller about an assassin hiding in an Italian village, but its deliberate pacing, minimal dialogue, and rich visual storytelling reveal a deeper psychological study. This review explores the film's complex psychological landscape, examining the character of Jack/Edward through multiple lenses, and analyzing how the film's visual elements and relationships contribute to its thematic exploration of isolation, identity, and the possibility of redemption.

The Psychology of Jack/Edward

Identity Fragmentation

At its core, "The American" is a character study of Jack (also known as Edward), a seasoned assassin and weapons specialist who seeks refuge in a small Italian town after a job goes wrong in Sweden. His psychology reveals several key dimensions:

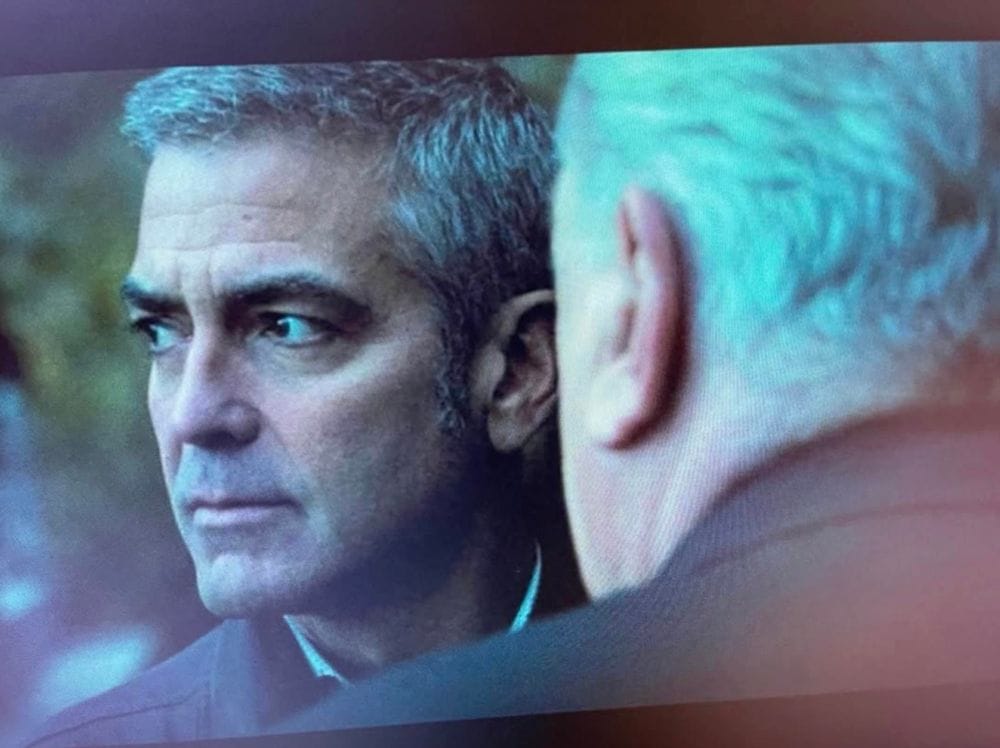

Jack exists between multiple identities - professional killer, weapons craftsman, and a man seeking connection. This fragmentation manifests in his sparse dialogue, controlled movements, and the stark contrast between his precision at work and awkwardness in human interaction. George Clooney's restrained performance brilliantly conveys this internal division, stripping away his usual charisma to portray a man living behind carefully constructed walls.

Hypervigilance and Trauma

Jack displays classic symptoms of hypervigilance throughout the film. His constant scanning of environments, sitting with his back to walls, and suspicion of every interaction point to someone living with significant psychological trauma. This state of perpetual alertness prevents authentic connection.

The opening sequence in Sweden establishes this immediately - what begins as an intimate moment is shattered by violence, and Jack's immediate shift from lover to killer reveals the compartmentalization that defines his existence. His subsequent execution of the woman who witnessed this event, despite their apparent relationship, establishes the complete subordination of emotional connection to operational security in his psychology.

Emotional Isolation

Perhaps most striking is Jack's profound emotional isolation. His interactions are transactional and guarded. When the local priest Father Benedetto asks, "Do you think God will forgive you?" it highlights Jack's awareness of his moral position and longing for absolution.

Corbijn repeatedly frames Jack alone in shots, emphasizing the physical manifestation of his psychological isolation. His spartan living quarters, limited possessions, and reluctance to engage in casual conversation all reinforce his existence at the margins of human connection.

Jack as Intelligence Professional

While "The American" presents Jack primarily as an assassin, his psychology and operational methods closely resemble those of an intelligence professional in several key ways:

Tradecraft Expertise

Jack displays sophisticated tradecraft beyond mere killing. His counter-surveillance techniques, secure communications protocols, and identity management reveal deep intelligence training. The methodical way he establishes his cover in the Italian town shows a professional versed in deep-cover operations rather than just contract killing.

Compartmentalization

Jack's psychological compartmentalization is characteristic of intelligence professionals. He maintains strict boundaries between operational and personal aspects of his life—a self-protective mechanism common among those in intelligence. This explains his reluctance to form connections even when desired.

The film subtly suggests that years of this psychological splitting has taken its toll. The cracks in his compartmentalization begin to show as he develops genuine feelings for Clara, creating the internal conflict that drives the film's third act.

Operational Security (OPSEC)

Jack's hypervigilance isn't mere paranoia but disciplined OPSEC. His constant environmental scanning, changing routines, and limited electronic footprint demonstrate someone trained to survive in hostile territory. His periodic phone calls from different locations show classic intelligence communication discipline.

Asset Development and Management

His relationship with Clara follows patterns of asset development in intelligence work. He initially establishes a transactional relationship, gradually develops trust, and eventually forms a genuine connection—though still maintaining operational awareness. This professional approach to relationships reveals how deeply his intelligence identity has shaped his psychology.

Independent Operator Syndrome

Jack exhibits the psychology of a NOC (Non-Official Cover) operator or independent contractor who has been in the field too long. His handler relationship appears to have deteriorated, and he operates with increasing autonomy and isolation—a dangerous psychological state for intelligence professionals. His statement that this will be his "last job" indicates his awareness that his professional psychology has become unsustainable.

The Visual Psychology

Corbijn's background as a photographer brings psychological depth through visual storytelling:

Negative Space

The film uses emptiness deliberately. Wide shots of Jack alone in landscapes or rooms create a visual representation of his psychological isolation. The Italian village, with its narrow streets and ancient architecture, becomes both haven and prison, reflecting Jack's constrained existence.

Precision and Control

The methodical weapon-building sequences mirror Jack's internal psychology - precise, controlled, and meticulous. This controlled exterior contains barely suppressed anxiety and fear. The camera lingers on the mechanical details, the careful measurements, and the testing procedures, providing insight into Jack's mind without dialogue.

The Italian Landscape as Psychological Canvas

The ancient Italian town serves as a counterpoint to Jack's psychology. Its history, community, and permanence stand in stark contrast to his transient, disconnected existence. The residents have roots and connections, while Jack remains perpetually in motion, unable to establish anything lasting.

Relationships as Psychological Mirrors

Jack's interactions provide insight into his psychological state:

Clara (The Prostitute Becoming Lover)

His relationship with Clara evolves from transactional to something more authentic. This relationship represents his tentative steps toward human connection, though his mistrust remains. The progression from paying for sex to genuine intimacy charts Jack's psychological journey toward vulnerability, but also highlights his difficulty in distinguishing between professional and personal relationships.

Mathilde (The Client)

With Mathilde, we see Jack's professional persona and paranoia justified. Their interactions highlight his inability to escape his professional identity. Their relationship is purely transactional, and her eventual betrayal confirms Jack's worldview that professional relationships ultimately reduce to survival and self-interest.

Father Benedetto

The priest functions as a psychological mirror, asking the moral questions Jack avoids. Their conversations about forgiveness touch on Jack's hidden desire for redemption. Father Benedetto represents the moral conscience Jack has suppressed, and their interactions suggest Jack's awareness of his moral compromise without offering easy absolution.

There's also an intriguing possibility that Father Benedetto himself may be more than he appears. Several subtle elements suggest he might be an intelligence professional or former operative:

- His immediate recognition of Jack as someone carrying secrets, despite Jack's cover story

- His pointed questions that demonstrate an understanding of violence and its psychological toll

- His comfort with Jack despite knowing he's dangerous, suggesting familiarity with such individuals

- The ease with which he navigates their cryptic conversations, never pushing too hard but always targeting vulnerable areas

- His statement about choosing the simple life in the village, which could reference his own past

- His penetrating observation to Jack that "You cannot doubt the existence of hell. You live in it," which suggests intimate knowledge of the psychological toll of operational life

If we view Father Benedetto through this lens, their relationship takes on new dimensions. Rather than merely representing moral authority, he becomes a reflection of a possible future for Jack—someone who has successfully transitioned from operational life to genuine connection with a community. His persistence in engaging with Jack could be read as professional recognition and an attempt to guide a fellow operative toward redemption rather than destruction.

The Butterfly Motif: Psychological Transformation

The butterfly tattoo on Jack's back becomes a central psychological symbol. It represents:

- The possibility of transformation

- The beauty and fragility of life

- Jack's suppressed desire to change his identity

This motif gains significance throughout the film, culminating in the appearance of an actual butterfly in the final scene, suggesting that Jack's transformation, while incomplete in life, might find completion in death.

Decoding the Ending

The ending of "The American" offers rich psychological complexity:

The Final Operation

Jack's final meeting with Mathilde represents the culmination of his professional paranoia and intuition. His correct assessment that she intends to kill him validates his hypervigilance but also confirms his inability to escape his professional identity.

The Butterfly and Transformation

As Jack drives to meet Clara after being wounded, the butterfly tattoo gains its full psychological significance. His decision to leave the rifle behind symbolizes his attempt at psychological transformation—abandoning his professional identity for a personal one.

River Symbolism

The final scene by the river carries multiple psychological meanings:

- The flowing water represents transition and change

- The natural setting contrasts with the constructed environments of his professional life

- The open space suggests vulnerability and an end to hiding

Psychological Interpretation of Death

Jack's death in the final moments can be interpreted as:

- The impossibility of escaping one's past identity

- The psychological price of transformation coming too late

- A form of atonement and acceptance

When he tells Clara "I'm coming" in his final moments, it suggests he has achieved a psychological peace despite physical death. His smile indicates a resolution of his internal conflict—he has chosen authentic connection over survival.

His death is not merely a plot point but the culmination of the film's psychological themes. The severity of his wound, his peaceful acceptance, and the symbolic transition represented by the butterfly all suggest that Jack's journey ends at the river. Yet this ending carries a form of redemption—he dies having made the choice for connection rather than continued isolation.

Conclusion: The American's Psychological Journey

"The American" presents a man trapped between identities, seeking connection while fearing it. The film's deliberate pacing, minimal dialogue, and visual composition create a psychological portrait of someone confronting the consequences of his chosen life.

Jack's journey is ultimately tragic. His attempt at transformation comes too late to save his life, but perhaps not too late to save something of his humanity. The film suggests that awareness of one's psychological state is only the beginning of transformation - actually changing remains profoundly difficult, particularly when one's identity has been shaped by years of violence and isolation.

What makes the film's ending particularly affecting is how it balances fatalism with agency. Jack makes a conscious choice to pursue connection with Clara rather than continuing his cycle of violence and isolation. Though the physical outcome remains the same, the psychological and spiritual significance of that choice gives his death meaning.

"The American" offers no easy answers about redemption or the possibility of escaping one's past. Instead, it presents a nuanced psychological portrait of a man who glimpses the possibility of transformation only when it's too late to fully realize it. The film's power lies in this ambiguity and in its suggestion that even small steps toward authentic human connection carry profound significance, even if they cannot ultimately save us.